The specificity to be universal: British social realist film culture and its evolving representations of the working class

- Lianne Yu

- May 1, 2024

- 28 min read

Abstract

The main purpose of this research project is to examine and explore the British social realist film culture and its evolving representations of the working class. This research project aims to understand how the specificities of various different filmmakers aid in the process of communicating their chosen relevant socio-cultural themes and issues to a wider audience demographic. This is important as British film culture has been described as an “unbroken tradition” by media and film scholar John Hill (2000, pp. 249). The aim for this research is to establish evidence on whether or not this statement still rings true to this day, with the exploration of the evolving themes and issues depicted in contemporary British social realist films. The methodological approach for this research project included comparative discourse analysis with the support of ethnography. During the process of carrying out this research, the films My Brother The Devil (2013) and The Kitchen (2023) have highlighted themes including but not limited to the ongoing housing crisis, life below the poverty line, and the inner conflicts of family relationships under these societal conditions. Through the displays of key events within the films’ narratives, real world events and personal experiences are reflected. From gathering information from the audience, interviews from the filmmakers, and reviews from film critics, the implications of these findings have proven that British social realism still remains to be an ever-evolving genre, without a clear cut definition. As British culture evolves, the films will always progress alongside, as new generations of filmmakers emerge and provide the audience with refreshing takes and relevant storylines, while the audiences take on the responsibilities to decode and interpret the meanings within.

Introduction

During the closing film premiere at the past year’s BFI London Film Festival, British director Daniel Kaluuya introduces his directorial debut in front of a 2700-seat auditorium with sincere personal realisations. Kaluuya stated, “you have to be very, very specific to be universal.” While explaining his thought process while creating the film, he said, “we have every right to be as unapologetic and as unashamedly ourselves,” in order to “tap into universal themes, stories and evolutions that everyone in the world can understand.” (Kaluuya, 2023). This statement perfectly captures the initial drive for this research project. The purpose of this research is to explore and analyse how films with such regional, mundane and niche narratives can impact and affect a much wider, international audience by scale. Furthermore, this research will aim to examine how multimedia language and key elements of film form have the ability to transcend language, geographical and even cultural barriers, as well as the notion of whether or not British film incorporates the notion of ‘universal language’ (Cromer, 1979, p. 107). Another main objective is to find out how the British film culture has, and potentially will continue to earn its currency in sincere, authentic portrayals of the working class and become key representations of the demographic, its statement on current events and how it will (or will not) hold the same social value in the near future.

Out of all British film genres, social realism has retained the most currency (Ramon, 2022). The rise of 1990s Brit-grit films pushed nuanced and relatable portrayals of the British working class to mainstream media, while its predecessor British New Wave (angry young men, kitchen sink realism) broke the taboo of exploring topics such as race, sexuality, and class divide during the late 50s to early 60s. Although contemporary social realist filmmaking has been critiqued (Lay, 2007), it remains an “unbroken tradition” to British film culture (Hill, 2000, pp. 249). The main question of how this film genre generated its worldwide impact could be answered through an investigation into how audiences respond to British cinema. Hall’s reception theory explores how media texts are encoded and decoded which provides a deeper understanding of the relationship between spectators and producers. Contextual analysis of not only the films themselves, but also of the production, distribution, audiences, etc can provide insight into the chain reactions and movements that occur following the release of certain films. To conduct research, a qualitative method is proposed. This will be a combination of comparative discourse analysis on two films - Sally El Hosaini’s My Brother The Devil (2013) and Daniel Kaluuya and Kibwe Tavares’ The Kitchen (2023); as well as ethnography which includes participants observation and individual informal interviews performed on-site at premieres of British films such as The Kitchen (2023) and Hoard (2023). This will provide in-depth information on the demographic, context on distribution,and offer insight into reactions of individual audiences.

Literature Review

Prior to conducting my own research, I reviewed a variety of previous literature on topics surrounding my questions. In order to begin, literature review is a helpful tool and an essential step which would allow me to identify data, findings and conclusions that can be beneficial towards my own primary and secondary research, as well as draw attention to any key areas and gaps that may have been under-researched by other scholars. I reviewed academic texts on important topics related to my query such as theories on the use and application of realism in film, British cinema’s concern in dealing with contemporary social issues, the importance of audience and representation in national cinema.

Social context and realism

In 1954, art critic David Sylvester proposed the concept of ‘The Kitchen Sink’ (Sylvester, 1954, pp. 61). The term was coined by Sylvester to discuss the works from well known British paint artists at the time such as John Bratby, Edward Middleditch, and Peter Coker, whose works revolved around the portrayal of ordinary people and even more so a celebration of their everyday lives. Their artworks conveyed social, cultural, and political implications which continued to evolve into film (as well as television) as the British New Wave became more dominant throughout the 1950s and 60s (Hill, 2000; Hutchings, 2009; Gardner, 2019), at its core, British social realism refers to a film movement which had emerged in post war Britain (Landy, 2009; Murphy, 2009). More recently, the terms ‘raw’ and ‘gritty’ (Lay, 2002, pp. 10) have often been used to describe the aesthetic, look and feel of films in the social realist drama genre by filmmakers, audiences, and critics alike. Furthermore, Brit-grit’ has been termed by Venessa Thorpe (1999) in an article exploring “the renaissance of British cinema”, one of the most notable revivals of kitchen sink films in this new millennium (Brown, 2009; Chibnall, 2009; McFarlane, 2009; Murphy 2009; Nowell-Smith, 2012), this term was also used by key theorists such as John Hill (2000) and Samantha Lay (2002) when discussing the portrayal of working class realism in British film. Additionally, Karl Popper's notion of verisimilitude (1962) remains to be deeply valued and cogitated by social realist filmmakers (Nwonka, 2017). Although far from exclusive to British social realism since verisimilitude spans across various genres and filmmaking styles (Sánchez-Escalonilla, 1970; Maddock, 2020), verisimilitude does refer to the degree of realism or believability achieved within the narrative, characters, and settings of a film. This becomes especially important when the ability to tell full bodied, comprehensive stories and highlight themes which are not a part of the central plot can directly aid or hinder the expression of core principles and themes of a film, and subsequently the impact on audiences (Donald and Renov, 2008, p. 454-455). Audience representations in British social realism reflects commitment to authenticity, social justice, and a nuanced portrayal of diverse experiences. Notable examples of contemporary British realism works include Shane Meadows' midlands realism This Is England (2006) which highlighted representations of the local youth’s coming of age, the skinhead subculture as individual vs. collective identity, and grief from the Falklands war; Ken Loach's social realism I, Daniel Blake (2016) which highlighted themes of poverty, inequality, and dignity, representing civilians living under a bureaucratic, dysfunctional welfare system; Andrea Arnold's Poetic Realism Fish Tank (2009) represented mother-daughter dynamics in fractured families, with themes of female empowerment, sexuality, and rebellion. Academic discussions about British social realism encompass a variety of elements that define the genre, this chapter will aim to unpack the meanings of social realism and explore this in the context of British film culture.

British social realism emerged as a significant cinematic movement in the post-war era, reflecting and responding to the profound social and economic transformations taking place in the aftermath of World War II (Landy, 2009; Murphy, 2009). The roots of this movement can be traced back to the late 1940s, gaining considerable momentum in the subsequent decades, particularly during the 1950s and 1960s (Hill, 2000; Morphet, 2003; Gardner, 2019). The dissemination and commercialisation (Hutchings, 2009) of British social realist films has its roots in post war Britain. During that time, filmmakers utilised this medium as a tool to respond to the economic and social shifts at the time, with this saw the British New Wave movement gain momentum in the mid 1950s, with its ten key film releases: Room at the Top (1959), Look Back in Anger (1959), The Entertainer (1960), Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1961), A Taste of Honey (1961), A Kind of Loving (1962), The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962), The L-Shaped Room (1962), This Sporting Life (1963) and Billy Liar (1963) occurring between 1959 - 1963 (Zarhy-Levo, 2010). Furthermore, realism is the core principle of social realism. The primary objective of social realist filmmakers is to capture life in its most authentic form. This has developed into a key convention for social realist films as being ‘raw’ and ‘gritty’ (Lay, 2002, pp. 10), which involves the showcase of day-to-day experiences, challenges, and joys of regular citizens. Instead of presenting a sensationalised or exaggerated version of life, the emphasis is on portraying the mundane and ordinary aspects which make up the fabric of day-to-day existence.

Exploration of social issues through film form

French film critic and theorist André Bazin (Morgan, 2006; Grosoli, 2011; Allen, 2014; Kim, 2017) suggested that realism, in the context of filmmaking, should supply enough room for the spectator to actively discover their own realities and piece together their individual interpretation of the narrative. Bazin also believed that realism in film can only be constructed through aesthetics, and that “there is not one, but several realisms” (Lay, 2002). He argued that specific cinematographic techniques such as long takes and wide, establishing shots could best capture and create opportunities for the spectator to fully navigate and absorb the realism in the film. A key component of British social realist films is the exploration of social issues, which would serve as a powerful tool for social commentary. From a filmmaker’s lens, the social realist genre has the potential to provide a distinctive perspective through engaging with socio-political realities. The London, Lewisham based film director Luna Carmoon claims that “Everything I write is based on real life” (Film4, 2020), this engagement goes beyond mere fictional storytelling as it involves a critical analysis and deliberate examination of past and current social affairs. This is characterised by the filmmaker’s commitment to the representations of the authentic and often gritty realities of the mundane and this cinematic approach primarily focuses on the working class and marginalised groups in society. Harkening back to the telling of universal themes through being specific, Carmoon’s work is heavily based on her own personal life experiences and the relationships she has built around her. Through her films Nosebleed (2018), Shagbands (2020), and Hoard (2023), Carmoon offers spectators a nuanced understanding of the challenges faced by individuals and communities, with a focus on gender dynamics such as motherhood, gender roles, feminism, and the intersection of gender and class. Carmoon is also intentional with the casting process of her films, non-professional are often casted to highlight the realism of performances.

Working class narratives, urban settings and regional identity

According to Nwonka (2017), British social realist films have long been intimately associated with aesthetic representations of ‘the other’. Especially in films with background mise en scene such as post-war housing, council estates, and city centre tower blocks. One defining feature of social realism lies in its portrayal of urban landscapes, where the dynamics of city life become central to the narrative. Through the lens of these films, spectators are granted a comprehensive view of societal issues embedded in urban settings, spanning across housing challenges and educational disparities to the intricate dynamics of communities navigating their shared spaces. From Housing Problems (1935) to The Kitchen (2023), there have been sincere attempts from filmmakers to represent sections of the British working class in an attentive and non derogatory way (Cuevas, 2008; Bell and Beswick, 2014; Beswick, 2019) through the usage of previously mentioned urban settings and housing territories, where the most potent social interactions of distinctive cultures take place and social identities, both individually and communally, are conferred (Nwonka, 2017). Paradoxically, the use of council estates as background settings highlights themes of resilience, and celebrates the displays of survivorship from its residents required to navigate a plethora of challenges and complexities of their political and social circumstances (Beswick, 2014, p. 5-10).

There is more to Britain than just London. Some social realist films delve into regional identities, the regional specificity embedded in some British social realist films further enhances the cinematic examination of working class life. These films delve into the unique, and perhaps isolated challenges faced by communities in specific geographic locations, providing nuanced perspectives into their socio-cultural landscape. This regional focus not only adds depth to the narratives but also contributes to a broader understanding of the diverse experiences within the working class. An example of this is British director Clio Barnard, whose works are mostly based in her native Bradford, West Yorkshire. Barnard’s filmography such as The Arbor (2010), The Selfish Giant (2013), and Ali & Ava (2021) all have common themes of portraying the working class life of people living in post-industrial, post-Thatcher northern England (Calhoun, 2013; Moore, 2021). Barnard's films are deeply rooted in specific regional settings, and the choice of location is not arbitrary, it serves as a backdrop that significantly influences the narratives and characters. The regional specificity adds a layer of authenticity and depth to the stories being told. Regional realism extends beyond physical settings in the background, instead highlighting the importance of location in the film’s narrative by bringing it to the forefront, using this device to delve into the intricacies of community dynamics and interpersonal relationships within the chosen region. Furthermore, Barnard's works have often been compared to Ken Loach (O’Hagan, 2013; Woodward, 2013; Stolworthy, 2018; Russell, 2023) - also a British social realist filmmaker who directed Cathy Come Home (1966) which was a significantly influential piece of social realist media about homelessness. The comparisons of both directors are mainly generated from their films Kes (1969) and The Selfish Giant (2013), where both share common themes of poverty, stealing, and symbiotic relationships between a young boy and an animal. Both directors often produce films which are regional specific, this approach allows their films to serve as authentic representations of the regions they depict, which have manifested into powerful commentaries on broader social issues.

Evolution to contemporary relevance and influence on audiences

According to Landy (2014, p. 51-52), film genres respond to and engage with evolving social circumstances and shifting audience dynamics. Over the past three decades, scholars and analysts examining British cinema have actively participated in a continuous discourse on the reassessment of the British New Wave. This ongoing debate revolves not only around the question of whether these films should be considered a cohesive collective (Hill 1986; Higson 1996) or conversely as noticeably different from one another (Hutchings, 2009, p. 305), but also extends to discussions on the degree to which they influenced subsequent developments in British cinema (McFarlane 1986). Regardless of the stance taken in these deliberations, the controversies themselves serve as indicative evidence of the profound significance attributed to these films as a pivotal axis in the evolutionary trajectory of British cinema. Zarhy-Levo (2010) suggests a connection to the Free Cinema movement of 1956, which was co-founded by Lindsay Anderson, Karel Reisz, Tony Richardson, and Lorenza Mazzetti. This movement emerged as a response to the belief, expressed by McFarlane (1997), that mainstream British cinema was conservative, confined by class distinctions, and lacked innovation. During that era, there was limited progress made in the commercial film industry.

The impact of social realist films extends beyond the confines of cinema screens, films contribute to an increase of public awareness and discourse, which stimulates conversations on social issues (Tudor, 2013, p. 74-102). In certain instances, these works have influenced policy debates and impacted public opinions. A totable example of this is the UK cinema ban of Rapman’s Blue Story (2019). The film faced a nationwide cinema ban after several violent incidents erupted during selected screenings, prompting Vue and Showcase chains to temporarily remove the film (Baggs; Campbell, 2019). With the film exploring themes of kinship, brotherhood, and gang violence, it drew attention for its portrayal of London gang culture. The controversy ignited policy debates on relevant topics such as censorship, cinema responsibility, and the potential influence of media on real world actions. Some viewed the ban as an overreaction, while others saw it as a precaution. Following discussions, the film was reinstated with heightened security measures, prompting reflections on cinema's role in societal discourse and the challenges of depicting sensitive subjects.

Methodology

The primary methodological approach used for this research project is qualitative discourse analysis. The concept of viewing film as a text has been a longstanding tradition in film theory, explored since its inception (Wildfeuer, 2016, p. 8). The thoroughness of the understanding of a film has direct links to the depths to which an audience can uncover the social, cultural, and political aspects embedded in discourse (Donald and Renov, 2008, p. 454-455). Therefore, delving into the intricacies of film language and communication is particularly useful for researchers when it comes to exploring and interpreting the ramifications of everyday human interactions in communities within more extensive societal contexts. Specifically for this research project, a comparative discourse analysis approach is proposed. In film studies, discourse analysis involves examining the language and communication strategies employed within films to understand how meaning is constructed, conveyed, and negotiated. It extends beyond verbal communication such as dialogue and script to include visual elements, gestures, symbols, and other semiotic elements present in a film. Discourse analysis in film studies is a multidisciplinary approach (Zaichenko, 2019) that draws on theories from linguistics, semiotics, sociology, and cultural studies. It provides a framework for examining the relationships between language, power, and identity within the cinematic medium, shedding light on the complex interplay between filmic representations and the socio-cultural contexts in which they are produced and consumed. The purpose of this research is to examine how contemporary representation of the working class is evolving and developing through time, and with Lay (2002)’s proposed concept of multiple realisms, a comparative study deemed to be the most appropriate choice. The main objective in discourse analysis is to explore the underlying ideologies, power structures, and social constructions embedded in the cinematic language, which would include how a film’s narrative and its characters highlight the themes audiences could identify, as well as the differences and similarities between two films and their respective key events and themes. Performing a comparative study on two thematically similar films could also enable the exploration of how different filmmakers with different technical styles decided to portray important socio-cultural issues. In this instance, both My Brother the Devil (2012) and The Kitchen (2023) share similar themes of family - displaying the inner conflicts of a father/son or a younger/older brother relationship; highlighting the recent housing crisis in London; and focus attention on the ever changing multiculturalism in London.

Additionally, ethnography is also used. As another data collection method for this research project, ethnography entails the researcher openly (overt) or discreetly (covert) engaging in the daily lives of individuals over a set period of time. During this time, the researcher will observe events, listen to conversations, conduct both informal and formal interviews, and gather any supporting and useful evidence such documents and artefacts - essentially collecting any available data that could help shed light on the emerging focal points of the research questions (Hammersley and Atkinson, 2007). One of the reasons this method was chosen is due to my London inhabitancy, which has allowed me valuable geographical access to the London film scene with ease. During the process of data collection, I have attended the British Film Institute's 2023 London film festival in order to be fully immersed amongst the stakeholders to my research question, key groups of people who could heavily impact my research and findings such as filmmakers, critics, students, fans, etc. In some ways, ethnography aligns to this paper’s opening statement on the notion of specificity, as this method allows for a more direct approach to knowledge which would enable a deeper understanding of the individual spectators’, general audiences’, and communities’ spheres. On one hand, this method aids in providing insights on the audience side of this research question. Specifically for this research question, when exploring themes of representation and film culture, it is important to consider the film texts themselves as well as the audience reception. A key element to approaching this research in the most multifaceted and well rounded way as possible is to consider a multitude of perspectives. Not only can ethnography generate in depth knowledge and understanding on topics surrounding this research question such as target demographics, personal and/or communal effects on audiences, lasting cultural impact of films, etc, it can also provide the opportunity to gain understanding into the firsthand experiences of individuals engaged in a specific activity, as well as the meanings they personally create in connection to it. Furthermore, this method entails the researcher's active immersion in the subject of their study, which would by nature lead to the researcher problematising knowledge relations between the investigator and investigated, critically analysing not only the data collected, but also how the method and process would play a part in the quality of the information gathered. However, there are some limitations to using ethnography when it comes to research for this project. Due to the nature of my research areas being focused on the individual’s personal experiences, and how participants may relate their own stories from a first person point of view to much bigger, culturally significant events in society, the raw data collected will be biased. As an attempt to rectify this to avoid exclusion and gain insight from a wider range of people, random sampling was used. Specific methods used to collect data in this ethnographic approach included informal interviews and participant observation.

Participant observation ‘involves data gathering by means of participation in the daily life of informants in their natural setting: watching, observing and talking to them in order to discover their interpretations, social meanings and activities’ (Brewer, 2000, p. 59). This method entails the researcher learning from, as supposed to learning about. Essentially, the data is collected through lived experiences, which requires the researcher to physically be near or within the space of the topic of research. In this instance, participant observation meant attending film festivals, screenings, premieres, Q&A sessions by filmmakers, etc. Being at events where the films are being actively consumed, perceived, and criticised would lead to the researcher being able to seek meaning through the participants themselves. This method, in comparison to other non ethnographic and more passive methods, proves to be more open ended and flexible. This is especially beneficial toward this research project, as audience reception, reactions, and the impacts of film cannot be rigidly measured, and quantitative data cannot cover all important aspects of my research questions. Therefore, pursuing both overt and covert observation in participants’ day to day settings could ensure versatile and well proportioned research findings.

Research Findings and Discussion

An Exploration of Conflicted Masculinity in My Brother the Devil (2012)

My Brother the Devil (2012) marks the directorial debut of Sally El Hosaini. It is a British social realist drama film, telling the story of a duo of brothers who come from an Egyptian immigrant family as they navigate the journey of coming of age in east London. The film's promotional poster encapsulates El Hosaini's conceptualization of protagonists Mo and Rash, portraying them as analogous to a DNA strand. The imagery represents two strands of helices, spiralling independently but interconnected. This suggests that our two brothers are on their own individual trajectories while remaining inextricably linked in narrative. This conceptual framework is integral to her screenplay structure, showing where each character oscillates between the dichotomies of criminal and gang culture, Egyptian and London identities, and acceptance of their sexuality. This metaphoric image serves as a thematic guide, symbolising the intricate connection between the characters' contrasting worlds and the tension that is inherent to their co-existence. This analysis will aim to decode the meaning of this text by examining two key scenes of this film - the opening sequence (00:00:00 - 00:07:00) and the street fight sequence (00:24:00 - 00:27:00).

(My Brother the Devil, 2012)

From the film's outset, the pervasive presence of Mo and Rash is evident in almost every shot composition, with a predominant focus on close-ups (CU) or point-of-view (POV) shots. This strategic visual approach seamlessly aligns with the film's subjective aesthetic and adheres meticulously to the 'four rules' collaboratively established by El Hosaini and her cinematographer (Heeney, 2015). By employing these carefully crafted rules, the film achieves an immediate and profound immersion of the audience into the subjective experiences of its protagonists, an approach discussed by Mary Ann Doane (2018).

The deliberate use of medium long shots (MLS) during the gym sequence is a noteworthy example, capturing Rash in sharp focus in the background while he observes a boxer's training session in the foreground. In this visual juxtaposition, Rash's facial expressions convey two crucial themes embedded within the film's narrative: the homoerotic nuances prevalent in male street culture and Rash's internal struggles with his own sexuality, as elaborated by Cherry (2017). This meticulous attention to visual storytelling not only establishes the brothers as pivotal characters but also provides a nuanced exploration of complex themes within the broader context of the film.

These key themes are also evident in a subsequent scene featuring Rash and his friends, depicted through group shots or two-shots displaying effortless physical intimacy in passing, such as the placing of arms around necks and the group play fighting. These scenes highlight the key theme of masculinity in the film, El Hosaini wanted to highlight the conflicts and juxtaposition between the alpha male, ‘no homo’ expression and the notion of being at peace with your sexuality (Heeny, 2015). Sayyid, a character who has left his ‘street’ identity behind and is now a photographer in the middle class, represents a kind of masculinity that juxtaposes the kind initially displayed by Rash. This is shown most dominantly during the dinner scene (00:50:00 - 00:51:21), where Sayyid shows that he is in touch with his ethnicity, displaying his own political conscience and mentioning listening to Arabic music as a hobby. This scene is also the only time Rash gains approval from his father, which implies what kind of ‘ideal’ man Rash’s father expects him to become.

(My Brother the Devil, 2012)

On the other hand, the presentation of an 'alpha male' persona by the male characters is a deliberate performance tailored for the approval of their peers. This is dominantly shown during the street fight sequence, where the alpha male performance would become dangerous and life threatening if undermined or contradicted. The director aimed to depict the individuals behind the stereotypical portrayal of urban youth wearing 'hoodies' (Bell, 2013), moving beyond the often negative depictions in news coverage and other films centred on urban settings. This objective gained added significance during the filming period when the London riots unfolded in 2011. The subsequent dehumanisation and demonization of young people in inner cities intensified the film's purpose of providing a nuanced portrayal. This approach stands in contrast to films like Sket (2011) and Kidulthood (2006), with the latter's script based on a compilation of sensationalistic tabloid headlines gathered by writer Noel Clarke over a year. The film fundamentally explores the theme of conflicted identity through the use of binary oppositions, delving into various forms of internal and external struggles and intricately examining the tensions and conflicts arising from the clash between different aspects of identity. These conflicts manifest in key themes and issues of the film, such as heterosexuality vs homosexuality; home life vs gang life; nobility vs crime; and lower class vs upper class.

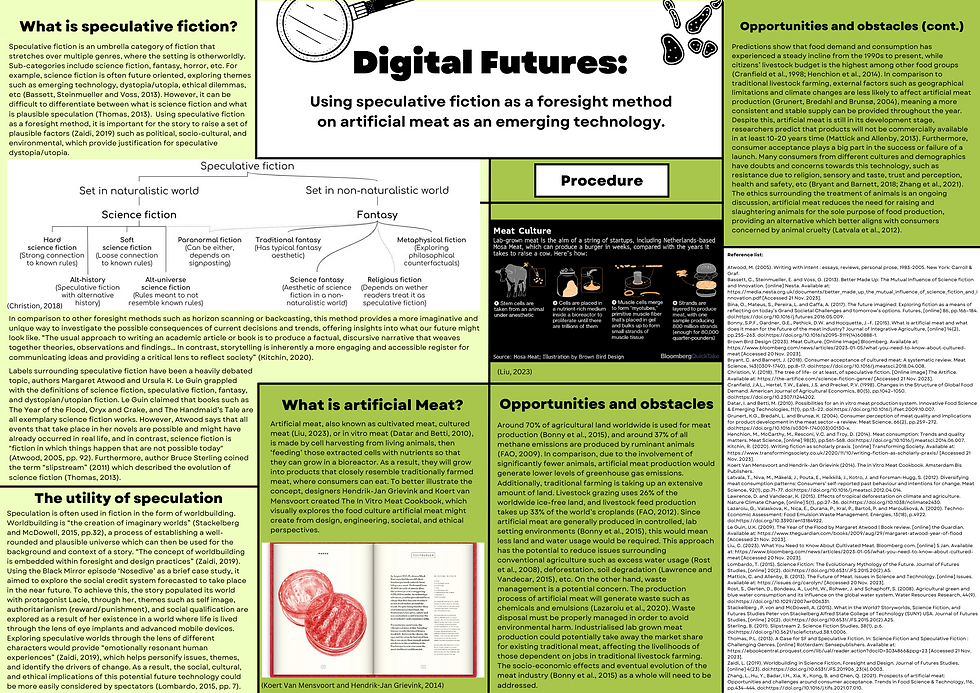

Dystopian resistance, unity, and community in The Kitchen (2023)

Tavares and Kaluuya’s The Kitchen (2023) tells the story surrounding a London housing estate in 2044 facing the imminent threat of demolition, with its bleak and nihilistic vision of London’s future evident, the film draws on current affairs and societal concerns. However, a strong sense of unity and community is shown through characters Izi and his son Benji, as well as all the other inhabitants of the council estate - ‘kitchen’. As a whole, The Kitchen (2023) is a dystopian sci-fi film following the genre conventions of a British social realist drama, the film addresses the imminent escalating issue of inaccessible and unaffordable housing, appearing almost prophetic. The film displays the premonition of possible future events as the divide between the rich and the poor continues to widen into significantly alarming extents. This section of the research will focus on two key areas, a textual analysis of the film itself with a focus on the opening sequence (00:00:30 - 00:05:20), supplemented with the findings surrounding audience reception, reviews, and participation during the premiere of this film.

(The Kitchen, 2023)

In the opening sequence, the close up shot of Izi's eyes looking wary of his surroundings not only establishes him as the protagonist, this impactful first shot also has connotations (Sap et al., 2017) to a prison-like environment. This shot composition symbolises the notion of confinement. This is also communicated by the use of steel and metal mise en scene and sound elements, metal gates and subsequently the sound of the scraping metal door suggest a certain degree of coldness and brutality. These visual codes emphasise themes of industrialisation and dystopian living. This is also a form of foreshadowing, as the scene progresses, the audience would come to find out that Izi is currently looking to move out of the ‘kitchen’ and into a middle class apartment complex with significantly better amenities. The combination of the use of low key lighting and steel interior highlights Izi’s initial mysterious presentation and his guarded demeanour. The utilisation of high contrast, overhead fluorescent lighting serves as a contributor to establishing a hospital-like environment, this is shown in both the establishing hallway shots and Izi’s shower scene. This lighting technique effectively showcases the harsh realities of the ‘kitchen’ residents’ dire living conditions through communicating clinical settings and infusing a sense of gloom and grime into the environment. Cross cutting between the residents impatiently waiting for Izi to finish using the communal bathroom and Izi alone inside the shower highlights some key differences - the theme of isolation vs community. Cross cutting between the two shots emphasise the juxtaposition of cool, blue tone lighting vs the warmer in comparison, chartreuse toned lighting. In this instance, blue represents isolation. Izi is a lone wolf character both inside the ‘kitchen’ and in the ‘outside’ world, struggling to fit in with either due to his conflicting identities of a person on the verge of ‘making it out the projects’. The chartreuse represents community, paired with a claustrophobic shot of the residents crammed in a narrow corridor whilst complaining about the wait for the bathroom, this highlights the theme of unity, no matter positive or negative, of the people living in the ‘kitchen’. Furthermore, the single red light in the shower is starkly different to the rest of the colour palette in this sequence. This is a foreshadowing device used to communicate a sense of impending doom, danger, and threat the residents are about to experience. As later on in the film, the same red alarm and sound design that occurred in this scene would be mirrored by a violent, deadly police raid.

(The Kitchen, 2023)

In the film, motorcycles serve as more than just a mode of transportation; they are powerful narrative devices that symbolise rebellion, nonconformity, and the act of taking risks. This symbolism juxtaposes against the abundance of cars found outside the ‘kitchen’. The deliberate choice of motorcycles over cars suggests a form of resistance to societal norms, perhaps not done willingly, as shown in the food stealing scene where a gang from the ‘kitchen’ are forced to steal food from a delivery truck in order to provide for their own community. Lastly, The visual composition of the title card scene adds another layer of meaning. The blue sky in the background appears in stark contrast to the dimly lit and over populated estate. This visual binary opposition creates a powerful metaphor, suggesting the potential for improvement or escape from the challenging circumstances depicted. The juxtaposition conveys a sense of hope amid the harsh realities of poverty and a housing crisis, hinting at the possibility of a brighter future. This interplay of symbols and visuals enhances the film's thematic exploration, reinforcing the narrative's underlying messages about societal struggles and the resilience of the human spirit.

Final thoughts and conclusions

Directors Tavares and Kaluuya intentionally chose London, the film's setting, as the debut location for their movie (Shafer, 2023), underlining its profound connection to the vibrant and diverse communities it portrays, particularly the working class Black British population. As I delve into the intricacies of these diverse cultures for my research, it is imperative to recognize my role as an outsider within these spaces. Despite my genuine intentions, a profound respect for the concepts, spaces, and frameworks inherent to these communities is essential.

During the film's premiere in London, a palpable sense of community and unity permeated the atmosphere, underscoring the profound impact of the film on its audience. This communal engagement aligns with Bazin's notion of film as a social documentary (Grosoli, 2011), emphasising the reciprocal relationship between filmmakers and audiences. The audience serves not only as a source of inspiration for the filmmakers but also as active participants in sparking conversations and potentially influencing policy debates within society.

At its core, the in-depth exploration of the intricate interconnections between social context and cinematic realism, coupled with a meticulous examination of socio-cultural issues embedded within the working-class milieu through nuanced film form, serves as a testament to the film's journey towards contemporary relevance. This evolution mirrors a dynamic engagement with the pulse of societal changes and challenges. The film's profound influence on its audience becomes emblematic of the symbiotic relationship between filmmakers and society, illustrating the potent capacity of cinema to not merely reflect but actively shape and influence meaningful dialogues and societal narratives. In this symbiotic dance between the filmmakers' narrative choices and the societal responses they elicit, the film emerges as a powerful catalyst, sparking conversations, challenging perceptions, and ultimately contributing to the ongoing discourse surrounding pertinent social issues.

Reference list

Allen, R. (2014). ‘There Is Not One Realism, But Several Realisms’: A Review of Opening Bazin. October, 148(1), pp.63–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/octo_a_00175.

Ashby, J. and Higson, A. (2000). British Cinema, Past and Present. 1st ed. Routledge.

Baggs, M. (2019). Blue Story: UK cinema ban called ‘institutionally racist’. BBC News. [online] 26 Nov. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/newsbeat-50543213 [Accessed 28 Nov. 2023].

Barr, C. (2022). British Cinema: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

Bateman, J. and Schmidt, K.-H. (2013). Multimodal Film Analysis: How Films Mean. [online] Google Books. Routledge. Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=ejTFiXcXB6YC&oi=fnd&pg=PR3&dq=bateman+and+schmidt+film&ots=3ZBHYndB_Q&sig=YwzN8kebIkjB9iOtwfpuMtWZOyQ&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=bateman%20and%20schmidt%20film&f=false [Accessed 23 Jan. 2024].

Bell, C. (2013). The Inner City and the ‘Hoodie’. Wasafiri, 28(4), pp.38–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02690055.2013.826885.

Bell, C. and Beswick, K. (2014). Authenticity and Representation: Council Estate Plays at the Royal Court. New Theatre Quarterly, 30(2), pp.120–135. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/s0266464x14000244.

Beswick, K. (2019). Social Housing in Performance. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Beswick, K.A. (2014). The Council Estate in Performance. pp.5–10.

Bradshaw, P. (2023). The Kitchen review – high-energy drama of near-future rundown housing estate. [online] theguardian.com. Available at: https://amp.theguardian.com/film/2023/oct/15/the-kitchen-review-daniel-kaluuya-high-energy-tale-of-near-future-rundown-housing-estate [Accessed 28 Nov. 2023].

Brewer, J.D. (2000). Ethnography. New Delhi Rawat Booksellers.

Calhoun, D. (2013). The Selfish Giant. [online] Time Out Worldwide. Available at: https://www.timeout.com/movies/the-selfish-giant [Accessed 25 Jan. 2024].

Campbell, L. (2019). Why Blue Story shouldn’t be banned from cinemas. [online] the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/news/shortcuts/2019/nov/25/blue-story-film [Accessed 25 Jan. 2024].

Cherry, P. (2017). ‘I’d rather my brother was a bomber than a homo’: British Muslim masculinities and homonationalism in Sally El Hosaini’s My Brother the Devil. The Journal of Commonwealth Literature, [online] 53(2), pp.270–283. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0021989416683761.

Cortvriend, J. (2017). Making Sense of Everyday spaces: A Tendency in Contemporary British Cinema. [online] Available at: https://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/19502/ [Accessed 28 Nov. 2023].

Cromer, J. (1979). Multi-Media: The Universal Language of a Global Society. The English Journal, [online] 68(7), p.105. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/814544.

Cuevas, S. (2008). ‘Societies Within’: Council Estates as Cultural Enclaves in Recent Urban Fictions. [online] brill.com. Available at: https://brill.com/display/book/edcoll/9789401206587/B9789401206587-s024.xml [Accessed 24 Jan. 2024].

Cuter, E., Kirsten, G. and Prenzel, H. (2022). Precarity in European Film. [online] Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. Available at: www.degruyter.com [Accessed 28 Nov. 2023].

Donald, J. and Renov, M. (2008). The SAGE Handbook of Film Studies. [online] Google Books. SAGE. Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=A9NX-vJqFy8C&oi=fnd&pg=PA454&dq=audience+understand+film&ots=KWjQbimFQS&sig=5qxZm2bHEAX4KpYYKRFlz-K2H5c&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=audience%20understand%20film&f=false [Accessed 23 Jan. 2024].

Dyer, R. (2002). The Matter of Images Essays on Representations. 2nd ed. Taylor and Francis.

Emelife, A. (2022). A brief history of protest art. London: Tate Publishing.

Film4 (2020). Behind-the-scenes of Luna Carmoon’s Shagbands. [online] Medium. Available at: https://medium.com/@Film4/behind-the-scenes-of-luna-carmoons-shagbands-88b7fb6b7c3f [Accessed 2 Dec. 2023].

Forrest, D., Harper, G. and Rayner, J. (2017). Filmurbia. London Palgrave Macmillan Uk.

Gardner, C. (2019). Kitchen sink realism and the birth of the British New Wave. pp.99–122. doi:https://doi.org/10.7765/9781526141583.00010.

Griffin, C.J. and McDonagh, B. (2018). Remembering Protest in Britain since 1500. Palgrave Macmillan.

Grosoli, M. (2011). André Bazin: Film as Social Documentary. New Readings, 11(0), p.1. doi:https://doi.org/10.18573/newreadings.73.

Hammersley, M. and Atkinson, P. (2007). Ethnography : principles in practice. New York: Routledge.

Heeney, A. (2015). SFFS Artist-in-Residence Sally El Hosaini on writing and directing My Brother the Devil. [online] Seventh Row. Available at: https://seventh-row.com/2015/02/15/sally-el-hosaini-my-brother-the-devil/ [Accessed 23 Jan. 2024].

Hill, J. (2000). From the New Wave to ‘Brit-Grit’: Continuity and difference in working-class realism.. In: British Cinema, Past and Present. Routledge.

Hill, J. (2011). Sex, class and realism. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Holub, R.C. (2013). Reception Theory. 1st ed. London: Routledge.

Hutchings, P. (2009). Beyond the New wave: Realism in British Cinema, 1959-63. In: The British Cinema Book. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kellett, L. (2017). Nostalgia in the British Cinema: The Significance of Nostalgia in the Social Realist Filmmaking Tradition with a Focus on the Work of Shane Meadows. [online] ray.yorksj.ac.uk. Available at: https://ray.yorksj.ac.uk/id/eprint/3284/ [Accessed 28 Nov. 2023].

Kim, T. (2017). André Bazin and ‘Cinematographic reality’. Trans-, [online] 3(1), pp.87–107. Available at: https://koreascience.kr/article/JAKO201731664587334.page [Accessed 24 Jan. 2024].

Landy, M. (2014). British Genres: Cinema and Society, 1930-1960. [online] Google Books. Princeton University Press. Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=QzwABAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=British+Genres:+Cinema+and+Society [Accessed 8 Nov. 2023].

Lay, S. (2002). British social realism : from documentary to Brit-grit. London: Wallflower.

Lay, S. (2007). Good intentions, high hopes and low budgets: Contemporary social realist film-making in Britain. New Cinemas: Journal of Contemporary Film, 5(3), pp.231–244. doi:https://doi.org/10.1386/ncin.5.3.231_4.

Littler, J. (2019). Mothers behaving badly: chaotic hedonism and the crisis of neoliberal social reproduction. Cultural Studies, [online] 34(4), pp.1–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2019.1633371.

Lodge, G. (2023). ‘The Kitchen’ Review: Kibwe Tavares and Daniel Kaluuya’s Impassioned Stand for Community Against Capitalism. [online] Variety. Available at: https://variety.com/2023/film/festivals/the-kitchen-review-kibwe-tavares-daniel-kaluuya-1235756595/amp/ [Accessed 9 Nov. 2023].

Maddock, D. (2020). Virtually Real: Cinematographic Verisimilitude within the Construct of Artistic Referentiality. Quarterly Review of Film and Video, 38(1), pp.1–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10509208.2020.1762476.

Mary Ann Doane (2018). The Close-Up: Scale and Detail in the Cinema. differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, [online] 14(3), pp.89–111. Available at: https://muse.jhu.edu/article/50602 [Accessed 25 Jan. 2024].

Moore, S. (2021). Tender is the North: Clio Barnard’s Gentle Cinema. [online] MASSIVE CINEMA. Available at: https://www.massive-cinema.com/storyboard/clio-barnard-features-ali-ava [Accessed 25 Jan. 2024].

Morgan, D. (2006). Rethinking Bazin: Ontology and Realist Aesthetics. Critical Inquiry, 32(3), pp.443–481. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/505375.

Morphet, J. (2003). New towns in the novel: a reflection on social realism. Planning Practice and Research, 18(1), pp.51–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0269745032000132637.

Murphy, R. (2009). The British Cinema Book. 3rd ed. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Murphy, R. (2019). British cinema of the 90s. 1st ed. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

My Brother the Devil. (2012). [Film] United Kingdom: BFI Player.

Nowell-Smith, G. and Dupin, C. (2012). The British Film Institute, the government and film culture, 1933-2000. Manchester, Uk ; New York: Manchester University Press.

Nwonka , C.J. (2017). Estate of the Nation: Social Housing as Cultural Verisimilitude in British Social Realism. In: D. Forrest, G. Harper and J. Rayner, eds., Filmurbia. Palgrave Macmillan.

Nwonka, C.C. (2023). Black Boys: The Social Aesthetics of British Urban Film. 1st ed. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Nwonka, C.J. (2014). ‘You’re what’s wrong with me’: Fish Tank, The Selfish Giant and the language of contemporary British social realism. New Cinemas: Journal of Contemporary Film, [online] 12(3), pp.205–223. doi:https://doi.org/10.1386/ncin.12.3.205_1.

Nwonka, C.J. (2020). The black neoliberal aesthetic. European Journal of Cultural Studies, [online] 25(3), p.136754942097320. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549420973204.

O’Hagan, S. (2013). Clio Barnard: why I’m drawn to outsiders – interview. [online] the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2013/oct/12/clio-barnard-selfish-giant-interview.

Parrino, F. (2023). Hoard: La recensione del film di Luna Carmoon . [online] The HotCorn. Available at: https://hotcorn.com/it/film/news/hoard-luna-carmoon-recensione-film-johnny-flynn-saura-lightfoot-leon-storia-trama/ [Accessed 8 Nov. 2023].

Paszkiewicz, K. (2023). The aesthetics of impasse and the affective rhythms of survival: Andrea Arnold’s Fish Tank as cinema of precarity. New Review of Film and Television Studies, [online] 21(3), pp.375–401. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17400309.2023.2218784.

Popper, K.R. (1962). Conjectures and Refutations : the Growth of Scientific Knowledge. London ; New York: Routledge.

Ramon, A. (2022). 10 great British social realist films. [online] BFI. Available at: https://www.bfi.org.uk/london-film-festival/lists/10-great-british-social-realist-films [Accessed 8 Nov. 2023].

Rasit, R.M., Hamjah, S.H., Tibek, S.R., Sham, F.M., Ashaaria, M.F., Samsudin, M.A. and Ismail, A. (2015). Educating Film Audience Through Social Cognitive Theory Reciprocal Model. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, [online] 174, pp.1234–1241. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.742.

Redmond, S. and Holmes, S. (2007). Stardom and Celebrity: A Reader. [online] Google Books. SAGE Publications. Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=5y2gOzdDojgC&oi=fnd&pg=PA65&dq=star+theory+film&ots=4KMNALzB8H&sig=9e-_8dVAGVp_yq_AeBQ11-cNzC0#v=onepage&q=star%20theory%20film&f=false [Accessed 25 Jan. 2024].

Rodríguez, L.G.V. (2017). (500) Days of Postfeminism: A Multidisciplinary Analysis of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl Stereotype in its Contexts. Revista Prisma Social, [online] (2), pp.167–201. Available at: https://revistaprismasocial.es/article/view/1599 [Accessed 28 Nov. 2023].

Russell, C. (2023). The indelible bond between Ken Loach and Eric Cantona. [online] faroutmagazine.co.uk. Available at: https://faroutmagazine.co.uk/the-bond-between-eric-cantona-and-ken-loach-pic/ [Accessed 25 Jan. 2024].

Sánchez-Escalonilla, A. (1970). Verisimilitude and Film Story: The Links between Screenwriter, Character and Spectator. Communication & Society, 26(2), pp.79–94. doi:https://doi.org/10.15581/003.26.36124.

Sap, M., Prasettio, M.C., Holtzman, A., Rashkin, H. and Choi, Y. (2017). Connotation Frames of Power and Agency in Modern Films. Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. [online] doi:https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/d17-1247.

Seino, T. (2010). Realism and Representations of the Working Class in Contemporary British Cinema. [online] De Montfort University. Available at: https://dora.dmu.ac.uk/server/api/core/bitstreams/7bfd704c-419b-4b25-9192-6dba5ed37954/content [Accessed 28 Nov. 2023].

Shafer, E. (2023). Daniel Kaluuya Premieres ‘Very British’ Directorial Debut ‘The Kitchen’ at London Film Festival: ‘One of the Best Days of My Life’. [online] Variety. Available at: https://variety.com/2023/film/global/daniel-kaluuya-the-kitchen-directorial-debut-london-film-festival-1235757090/ [Accessed 8 Nov. 2023].

Slater-Williams, J. (2023). ‘Hoard’ Review: An Audacious, Unsettling British Debut Announces a Singular Directing Talent. [online] IndieWire. Available at: https://www.indiewire.com/criticism/movies/hoard-review-venice-british-1234901975/ [Accessed 8 Nov. 2023].

Smyth, C.-P. (2019). Blue Story: A Moral Panic. [online] Birmingham Young Filmmakers Network. Available at: https://www.byfn.co.uk/post/blue-story-a-moral-panic [Accessed 8 Nov. 2023].

Staiger, J. (2005). Media Reception Studies. New York And London: New York University Press.

Stolworthy, J. (2018). Meet the director hailed as one of the most significant voices in British cinema. [online] The Independent. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/features/clio-barnard-dark-river-interview-film-ruth-wilson-the-selfish-giant-mark-stanley-trailer-wonder-woman-british-cinema-a8219371.html [Accessed 25 Jan. 2024].

Sylvester, D. (1954). The Kitchen Sink. [online] The Unz Review. Available at: https://www.unz.com/print/Encounter-1954dec-00061/ [Accessed 2 Dec. 2023].

Symeou, P.C., Bantimaroudis, P. and Zyglidopoulos, S.C. (2014). Cultural Agenda Setting and the Role of Critics: An Empirical Examination in the Market for Art-House Films. Communication Research, [online] 42(5), pp.732–754. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650214534971.

The Kitchen. (2023). [Film] United Kingdom: Netflix.

Thorpe, V. (1999). Reality bites (again). [online] The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/1999/may/23/1 [Accessed 2 Dec. 2023].

Tudor, A. (2013). Image and Influence: Studies in the Sociology of Film. [online] Google Books. Routledge. Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=M55WAgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=how+do+films+influence+society&ots=V9xeLrxC2W&sig=apSQ28ee-xhQeJBZBW7En6MHcL8&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=how%20do%20films%20influence%20society&f=false [Accessed 25 Jan. 2024].

Wildfeuer, J. (2016). Film discourse interpretation : towards a new paradigm for multimodal film analysis. London: Routledge.

Wood, H. (2019). Three (Working-class) Girls: Social Realism, the ‘At-risk’ Girl and Alternative Classed Subjectivities. Journal of British Cinema and Television, [online] 17(1), pp.70–90. doi:https://doi.org/10.3366/jbctv.2020.0508.

Woodward, D. (2013). Director Clio Barnard on The Selfish Giant. [online] AnOther. Available at: https://www.anothermag.com/art-photography/3148/director-clio-barnard-on-the-selfish-giant [Accessed 25 Jan. 2024].

Zaichenko*, S. (2019). Film Discourse As A Powerful Form Of Media And Its Multi-Semiotic Features. The European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences, [online] 66(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.08.02.74.

Zarhy-Levo, Y. (2010). Looking Back at the British New Wave. Journal of British Cinema and Television, 7(2), pp.232–247. doi:https://doi.org/10.3366/jbctv.2010.0004.

Zoonen, L. van (2007). Audience reactions to Hollywood politics. Media, Culture & Society, [online] 29(4), pp.531–547. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443707076188.

Comments